Apathetic Integrating of Art and Music in the Middle School

Abstract

Constructive strategies to learn nearly and appoint with climatic change play an of import role in addressing this claiming. At that place is a growing recognition that didactics needs to change in order to address climatic change, yet the question remains "how?" How does 1 engage young people with a topic that is perceived equally abstract, distant, and complex, and which at the aforementioned fourth dimension is contributing to growing feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety among them? In this paper, I argue that although the important contributions that the arts and humanities can brand to this challenge are widely discussed, they remain an untapped or underutilized potential. I then present a novel framework and demonstrate its use in schools. Findings from a loftier schoolhouse in Portugal signal to the central identify that art can play in climatic change educational activity and date more general, with avenues for greater depth of learning and transformative potential. The paper provides guidance for involvement in, with, and through art and makes suggestions to create links between disciplines to back up meaning-making, create new images, and metaphors and bring in a wider solution space for climate change. Going beyond the stereotypes of art as communication and mainstream climate change education, it offers teachers, facilitators, and researchers a wider portfolio for climate change date that makes use of the multiple potentials of the arts.

Introduction

At that place is lilliputian dubiousness that today'southward children volition inherit a earth with complex social-ecology challenges. Limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels is a major task that involves rapid and profound changes in how societies function. Educational activity plays a vital role in addressing this claiming and many have argued that it needs to be revised and restructured in guild to provide atmospheric condition for transformative learning and meaningful climate action (Monroe et al. 2017; O'Brien et al. 2013; Sterling and Orr 2001).

At schoolhouse, didactics about climate change normally takes place in the natural science disciplines and is often express to explaining the greenhouse effect and discussing the potential consequences of ascent temperatures, changing atmospheric precipitation patterns, and increasing sea levels (Monroe et al. 2017; Stevenson et al. 2017). Communicating mainly messages of fear rather than showcasing real examples for agile engagement, this approach has been criticized for contributing to feelings of denial, numbing, and aloofness (Norgaard 2011; Stoknes 2015). Non surprisingly, enquiry has institute that pessimism and hopelessness most climatic change and the future in general is growing amid young people (Ojala 2012). At the same time, in 2018, Greta Thunberg sparked an initiative among school children referred to as Fridays for Future motion because she provides a fresh perspective on the urgency of the climate challenge and signals the need for positive avenues for understanding and engaging the issue.

The arts and the humanities can play a critical office in engaging immature people and adults with new perspectives on climate change. At universities every bit well as at schoolhouse, humanities classes offering environments for disquisitional, integrative, and reflexive approaches and the arts disciplines including visual art, theater, and music can provide spaces for creative imagination, experimentation, and perspective-taking (Bentz and O'Brien 2019). Art tin also attend to and transform emotions, creating hope, responsibleness, intendance, and solidarity (Ryan 2016). Integrating arts-based methods and climate alter education and appointment tin can thus serve equally a means of expanding young people's imagination and empowering them to co-create new scenarios for transformative change.

Notwithstanding this potential, climate change is rarely integrated into the curricula of arts, music, literature, linguistic communication, and philosophy (Siperstein et al. 2016). Lilliputian research has been done on how to teach about the topic in the humanities and social sciences (A. Siegner and Stapert 2019), specially in elementary, secondary, and high school. This is despite the fact that a large body of research has shown that the engagement with sustainability-related topics at younger age has a college chance to lead to pro-ecology behaviors and attitudes (Barthel et al. 2018; Chawla and Cushing 2007). The touch of a given climate-art education project depends very much on the chosen approach and setting. Arts-based practices can be used in many different ways and volition consequence in different depths of engagement.

In this article, I propose a framework that distinguishes 3 levels of arts-based date with climate change and their potential application to educational activity. Integrating climate change in arts courses, expressing with art, and learning through art can prepare and empower immature people to accost climatic change themselves and add to the electric current discourse in a style natural sciences lone are unable to reach. The proposed framework, aimed towards teachers, practitioners, and researchers working with young people, draws insights from scholars of education for sustainable evolution, transformation, art, and critical thinking among others likewise as from a case study in a Portuguese loftier school, which volition exist discussed beneath.

The objective of this article is not to provide an "creative recipe" for climate change didactics. Rather, it intends to clear and reverberate on the potential of art and educational practices to prepare and empower young people to address complex global challenges and contribute to the broader soapbox on climatic change and societal transformation. At that place is need for further research to better understand the contributions of teaching climate change in, with, and through the arts and the applicability of the tentative framework in diverse schoolhouse settings. Nonetheless, this study articulates some insights that tin complement existing frameworks for education on sustainable development, critical thinking, and climate change.

Climate date in, with, and through art

Art and arts-based practices are increasingly seen equally a powerful style of developing meaningful connection with climate change (Bentz and O'Brien 2019; Shrivastava et al. 2012). Artistic and creative practices and approaches tin can help aggrandize our imaginaries of the future, opening up our minds to new scenarios of change. Art'south potential to transform social club, as well as its capacity to support agency and inspire feelings of hope, responsibility, and care, has been known for a long fourth dimension (Boal 2000) and esthetic practices tin can contribute to deep emotional learning about sustainability. For example, artistic practices can create openness towards more-than man worlds, providing access to different sources of cerebral, emotional, and sensual experiences (Pearson et al., 2018).

Art has the chapters to raise awareness, to engage creativity for addressing complex problems, and may also support transformation to sustainability (Dieleman 2017). Nonetheless, the impact and outcome of a given climate-art project depends on the very nature of it.

Here, I advise a framework for understanding and guiding arts-based practices to be used in different ways and for fostering different depths of date of a given target group of participants and audiences (see Table 1). In the following section, I illustrate the three depths of date in climate change depicted in Table ane, including in art, where art is used every bit a platform for introducing or communicating the issue; with art, where art serves as a medium to facilitate dialogue and express learning; and through art which conceptualizes art every bit a ways of transformation. Transformation has been conceptualized as a change in societal systems, structures, and relationships, and carries with information technology a promise of moving the world towards equity and sustainability (O'Brien 2012).

Climate engagement in art

Art can be a powerful tool for communication. Within the growing field of scientific discipline advice, art has been identified as an constructive ways of communication to raise awareness with the help of video work, documentaries, infography, illustrations, and comics nearly climate change impacts and adaptation strategies (Roosen et al. 2018). Many of such approaches rely on the visual engagement of fine art, based on the well-known saying "a motion picture is worth a 1000 words". Here, art is supposed to enrich the narrative and extend its attain. Information technology is used in an instrumental manner to communicate climatic change or projection results in a more attractive, potentially less serious and more understandable mode without shaping or questioning primal methodological approaches or systemic givens (Shush et al. 2018; Yusoff 2010). It is often the instance that the predefined settings and boundaries of a research project or public consequence wishing to present art get out limited infinite for creative expression of artists. Artists have engaged in such collaborations, using fine art as a platform to introduce and communicate nearly climate change.

A growing number of artists are interested in and concerned about climate change and environmental degradation (Gabrys and Yusoff 2012; Lesen et al. 2016). Emerging from the field of ecological art since the 1970s, artistic engagements with climate change accept grown considerably. A common approach of many artworks has been to focus on or document the issues, run a risk, and impacts of environmental problems; they communicate climatic change, as a topic in the arts. This mode of using art to introduce and communicate about climate change has attracted more than and more than critique considering it rarely leads to pro-environmental behaviors and might even have contributed to feelings of powerlessness (Moser and Dilling 2011). Another reason for artists' appointment in climate communication may be related to limited funding opportunities of more than experimental, open up-ended and arts-led research projects. In comparison with the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities continue to concenter a much smaller corporeality of research funding for climatic change mitigation (Overland and Sovacool 2020). Climate projects where arts play a dominant or equally important role as natural sciences are even so limited.

Artworks resulting from collaborations in which arts play a subordinate part, in the sense of communicating project outputs or predefined climate change impacts and accommodation measures, do not fully unleash the potential of arts to contribute to new ways of seeing and acting upon climate change. Nevertheless, this use of art is important to provide more aesthetic, attractive, and easily accessible ways of communicating the complexities of climate alter to broad audiences.

Climate appointment with art

Climate engagement using creative, creative practices has the potential to become beyond science communication and help people to overcome perceived psychological distance and develop critical thinking. Formerly limited to galleries and laboratories, art and science interactions have go commonplace inside social, political, economic, and ecology contexts outside of conventional institutions (Latour, 2004). This shifted the traditional sender-receiver paradigm by, for example, engaging communities in artistic-participatory processes (Hawkins 2016). Participatory art has the potential to bring together people from dissimilar sectors and contexts, supporting dialogue and the cosmos of networks amidst artists, scientists, and gild. Such arts-based practices can facilitate dialogue, which can then lead to the cultivation of deeper understanding.

Creativity, inspiration, and positive stories are powerful means to explore applied solutions for addressing climate change (Veland et al. 2018). Experiential projects such as artistic hands-on labs or fieldtrips can make climatic change experience real and near for diverse audiences past providing sensorial experiences and emotional connection (Hawkins 2016; Hawkins and Kanngieser 2017). Fine art can help facilitate a creative appointment with the topic and the expression of new insights and learnings of a participatory process (Burke et al. 2018). Such processes and collaborations between artists, scientists, and the broader guild are also useful for making micro-macro connections between private lives and the larger global context. Art's ability to keep open up the ambiguities, ambivalences, contradictions, and sometimes cluttered dimensions of reality, rather than leveling them into a coherent logical system, is seen as helpful when addressing the complexities of climate change (Kagan 2015).

Projects involving fine art and artists do good from art's adequacy to capture complex processes and problems as well equally its ability to mirror the unfolding nature of social life and limited the learnings of an interactive process (Leavy 2015). Such projects engage people in climate change with art and creative processes. Processes in which art serves every bit a medium to facilitate dialogue and limited learning are often appreciated due to their engaging and potentially playful nature, which can bridge and integrate opposing interests and unlike forms of noesis. They are oft participatory, experiential, community engaging, and process every bit well as goal-oriented. Examples include art-&-scientific discipline labs and participatory fine art. Such processes that tap into the creative potential of all participants and reduce hierarchies of ways of knowing and have the potential to build community, which might be an important prerequisite for social transformation.

Climate date through art

Apart from facilitating dialogue and the expression of learning, fine art tin can operate on a profound, transformative level. Information technology can be a process that engages people with climatic change on a deep, emotional, and personal level. It has been argued that at its best, art can be emotionally and politically evocative, captivating, aesthetically powerful, and moving (Leavy 2015). For case, a theater on the experience of a forest burn can communicate emotional aspects of life in a way that creates a deep connection with the audience, evoking compassion, empathy, equally well as understanding and meaning. The cosmos of personal meaning usually involves more than the cerebral aspects of climate change. It requires the inclusion of upstanding, melancholia, and aesthetic knowledges, which affect how we interpret and assign value to sure aspects of our life (Castree et al. 2014). Arts practices allow multiple meanings instead of pushing authoritative claims by implying which meanings are considered relevant or correct. In that sense, a piece of visual art, for instance, tin be interpreted in many unlike ways depending on the viewer besides equally the context of viewing.

Some other way of creating meaning is through stories. Storytelling and writing are fundamental parts of human life. To a certain extent, we tell stories to give meaning to our lives (Bochner and Riggs 2014). Stories tin can brand us feel connected, open our eyes to new perspectives, stimulate self-awareness or social reflection. Through fictional writings, we tin express ourselves freely, reveal the inner lives of characters, and create believable worlds for the readers to enter (Leavy 2013).

Creative and creative practices can too include embodied experiences. This is especially relevant when we consider that all experiences are ultimately embodied and that information technology is through the senses that we come to know (Wiebe and Snowber 2011). Trip the light fantastic and theater, every bit particularly embodied practices, tin incorporate words and narratives. When we understand the trunk equally having meaning in itself, as opposed to a container where meaning is stored, we tin can apply it as a means to pose questions, connect with emotions, and understand theoretical concepts. This mode, dance and movement tin challenge norms that are embodied and rendered invisible. It can be argued that it is through the body that nosotros can see and experience differently. That existence so, dance has been attributed a transcendent, transformative potential (Leavy 2015).

Using fine art as a tool that guides us through a meaning-making and embodied experience is arguably a transformative process that can enable us to see and deed differently on climate change. According to Pelowski and Akiba (2011), in gild to be transformative, art needs to be confusing so that the viewer is forced to suit new information that does not fit his/her self-prototype. This leads then to a process where conceptions and worldviews are questioned and a cocky-alter of the viewer can occur (Pelowski and Akiba 2011). Processes in which art is used every bit a means of transformation are often open-ended, co-creational, and therefore procedure-oriented every bit opposed to output oriented. Results may too differ from initial expectations. Examples for such processes could be independently creating an artwork prompted past an open-concluded and personally relevant climate-related question, or co-creating a theater performance based on personal experiences.

Beingness hard to measure, there is limited knowledge nigh how to provide transformative experiences in climate change engagement processes that allow participants to question and re-evaluate their perspectives, values, and worldviews in a way to learn anew how to chronicle to the systems and structures that maintain the condition quo. Such processes frequently rely on the experience of the facilitators, artists, or teachers and their notion of successful tools (Funch 1999) only also on the receptivity of the engaged participants or students. Furthermore, they are potentially time-consuming.

The outcomes of engaging in climate change through arts may greatly differ from those of engagement in or with art in the sense that they potentially create a deep, long-lasting impact on the participants and audiences, which can and then enable transformations in the way they relate to, feel about, and act upon climate modify.

Data and methods

The insights of this article are drawn from multiple sources of data. Between 2018 and 2019, using qualitative research and embedded in a transformative research paradigm, I engaged 70 students anile between 16 and 18 years of a public fine art loftier schoolhouse in Lisbon, Portugal, in two different art and climate modify projects.

(1) Within projection Art For Change, two 11th-grade communication design classes (in 2018 and 2019) engaged in climate change past identifying i small modify that could be beneficial to the environment and committing to it for 30 days. During the 30-solar day experiment, they reflected in grouping dialogues, and fish-bowl discussions, writing exercises and through making art almost their detail relationship with climate alter every bit well as social norms, values, and systems.

(two) In project Cli-fi & Fine art, students of one 11th-form course (in 2019) engaged with climate change through Climate Fiction (cli-fi). In their English language classes, they read the brusk stories in "Everything Change: An Album of Climate Fiction" (Milkoreit et al. 2016) and expressed their feelings near the stories, climate change, and the future more generally in group dialogues. Within the communication blueprint classes, they developed an art project about their particular interaction with the topic.

Both projects were designed as reflexive, experiential, and open up-concluded learning processes. Over a period of iv–v months, within each class, students reflected individually and in groups on climate change past connecting behavioral changes and practical actions with larger systems and structures, as well every bit past examining individual and shared beliefs, values, and worldviews. In ii interactive lessons for each class, students learned about observed and futurity climate change impacts besides as what kind of responses existed and could be imagined. They discussed how these would affect them and how they could influence them. In grouping dialogues and fish-bowl discussions, students could share their thoughts and feelings forth the learning process as well as new insights virtually themselves and well-nigh climate change. They further discussed similarities and differences in their experiences. Parallel to the reflection and learning process, students started sketching and conceptualizing their private art project. Each student developed an artwork related his or her personal subject of interest, point of view, new insight, or individual process of reflection related to climate change. The process of making the artworks (silk print, stencil, drawing, aquarelle painting, digital epitome edition using Illustrator and Photoshop) was led by the art teachers of the school, even so the teachers' guidance was of technical nature related to the realization of the artworks and did not influence the ideas of the students' artworks. The resulting 63 artworks and 33 written artist statements were exhibited in a local sustainability festival in Telheiras, Lisbon (2018 edition, Art For Alter), and at the European Climate Change Accommodation conference in Lisbon (2019 edition).

As a methodological arroyo, I used participant ascertainment, took notes, and facilitated grouping dialogues and fish-bowl discussions. The group dialogues and discussions were recorded. Recordings were transcribed, and transcripts, notes, and students' written reflections and artist statements were so coded. Coding is a heuristic and exploratory trouble-solving technique that can encompass a various range of qualitative data including transcripts of discussions, field notes, and visual data (Saldaña 2016). A code book was adult to define the meaning of each code and create categories of codes. Specific codes were assigned to the data using NVivo (version 12).

Analytic memos were written to reflect on code choices and their operational aspects. These information were used to identify emergent patterns and possible networks amidst the codes and categories. The artworks were analyzed using a holistic interpretive lens guided by intuitive enquiry and in connection with the creative person statements. The intuitive impressions and holistic interpretations of the images were documented in analytic memos. And then, the brownie of the visual reading was assessed through supporting details from the artworks—testify that affirmed or disconfirmed the personal assertions. Codes were and then derived based on the interpretative essence of the image, a method suggested by Saldaña (2016).

Through this procedure, I noted how climatic change seems to be a challenging topic in education settings. Despite enormous corporeality of data on the changing climate, effective teaching strategies are all the same limited, especially ones that empower young people (Monroe et al. 2017). While carrying out this written report on art and climate, I realized that there was more than ane mode to make the links between climate and art, and that different ways of involvement had an impact on how the students engaged with climate change. Moving between my data collection and the artworks in a preliminary analysis, I began to note the categories of how art was being used in climate alter education and with what effect. Based on this abductive enquiry, carried out in relation to the scholarship on this topic and in consideration of the data generated by this written report, I present a newly adult framework for using art in climate modify appointment and pedagogy (Tables 1 and 2). My inquiry suggests that researchers and teachers may exist able to make use of this framework on the potential of art to appoint more deeply with climate change in social club to provide conditions for meaningful learning and climate activeness.

Learning almost climate change in, with, and through art

In most countries, climate change is role of the natural sciences curricula, which usually approaches the topic from a positivist science point of view, presenting climate change as an environmental trouble related to increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the temper as a event of human activities (Hess and Collins 2018; Schreiner et al. 2005). It has been argued that this soapbox fails to address some of the elements that reinforce the status quo. Nor does it consider the possibility of private and commonage agency to dramatically change current systems, patterns of consumption, and resource use (Kirby and O'Mahony 2018; Leichenko and O'Brien 2019; Verlie and CCR 15 2018).

The students in this research engaged with climate change within arts and humanities disciplines. The projects were conceived every bit arts-led, transformative learning experiences that invited students to a reflexive, experiential, and open-ended learning process. Nearly of the students were receptive to embark on this experiment and were interested in climate change. Yet the results show that at that place are different depths of appointment in climate alter. This may depend on a number of factors including the chosen arts-based arroyo—whether climate change is simply dealt with in arts disciplines, with artistic-participatory practices, or learned or guided through an art process (Table 2). Drawing from the tentative framework of the depths of aesthetic climate involvement (Tabular array i), the following give-and-take, I portray these depths of appointment through fine art in the context of climate change teaching, illustrated with data from 2 different climate-art-education projects. I besides provide suggestions for how to apply them to a school setting. Whereas the in a higher place described characteristics and modes to engage with climate change (and Tabular array 1) tin can occur in a variety of fields of practices, the post-obit discussion applies specifically to an educational activity context.

Learning virtually climate change in arts and humanities classes

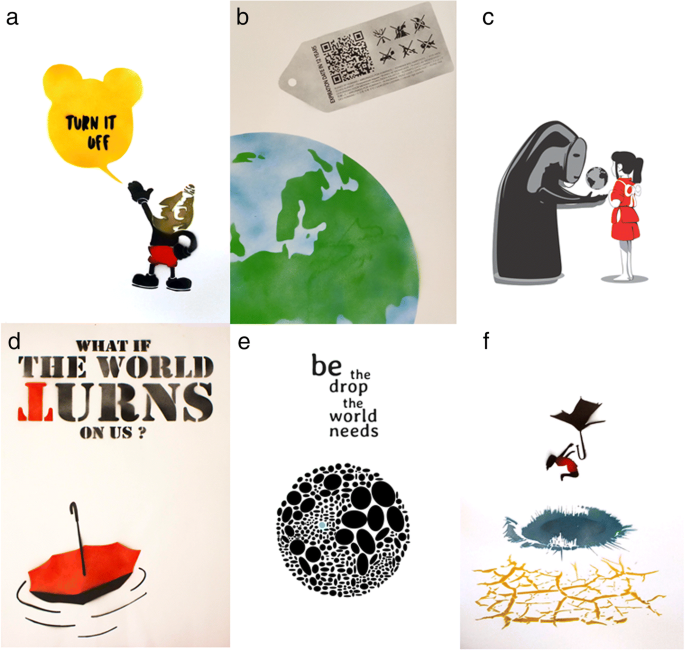

More and more arts and humanities educators explore climate change as a topic within their classes (Monroe et al. 2017; A. B. Siegner 2018; A. Siegner and Stapert 2019). Unremarkably, they rely on teachings from the natural science disciplines and the biophysical discourse, for example, past reading informative texts about climate modify, watching documentaries, applying learning games or by using climate change every bit a theme for illustrations, paintings, or drawings (Climate Generation 2019; Cooper and Nisbet 2017; Dieleman and Huisingh 2006; Vethanayagam and Hemalatha 2010). Resulting artworks are often descriptive works, illustrative climate communication, and lack a disquisitional or personal reflection and interaction with the theme, equally in Fig. 1 a and b. The students of this research were introduced to the topic of climate modify through an interactive lesson. Due to limited time provided past the school, the focus of this lesson was climate change impacts too as possible solutions which runs the risk to paint a rather dark picture of the future. In the grouping dialogues and fish-bowl discussions, the focus was more on individual and collective action and on opportunities to human activity, nevertheless some students maintained an unattached, technical perspective on the bailiwick matter. This is as well illustrated by their associated statements that show that these students used (stencil) art to describe the issues of climate change (Fig. 1a) and a technical, arguably simplified solution (Fig. 1b):

My work was inspired by cartoons, and represents a light seedling. My goal is to alert people of the need for energy saving.

Student F, artist statement, Fine art For Alter project 2019

Artwork of projects Fine art For Alter and Cli-fi & Art 2019

The representation of the earth with a label with the expiration date of 12 years is the period of fourth dimension in which we can yet make difference and improve the critical state of affairs of the planet. With adapted symbols, I wanted to mention that the causes are human. The QR lawmaking will atomic number 82 the viewer to a site that explains climatic change, its causes, and consequences. With this work I intend to convey that if there is no change in our actions in these 12 years, the world can face up an irreversible destruction, and information technology is our responsibleness to modify our attitude towards this trouble.

Educatee Thou, artist statement, Cli-Fi & Art projection 2019

The students' artworks and statements show that their perception of climatic change is disconnected from themselves. Although they are aware of the problem, their statements relate to the perspective of the biophysical discourse that frames climate change every bit an environmental problem of greenhouse gas emissions. This more technical way of conceptualizing climate change runs the take a chance of disempowering students because of a limited consideration of private and collective agency to change systems inside this discourse (Leichenko and O'Brien 2019). The results advise that when the goal of a learning experience is to create more climate awareness (e.g., empowerment), information technology might not exist enough to teach climate change in the arts with the same approaches that are commonly practical in the natural science disciplines and utilize art as a platform of providing easily accessible data or communicating the problem. Rather, more than (co)artistic approaches are needed, some which hail from dissimilar discourses in order to build a young generation that is capable of addressing climate change.

For case, teaching climate modify in the arts and humanities courses can be done more than holistically, past cartoon on the integrative discourse. An integrative discourse sees climate change as interconnected with multiple processes of environmental, economic, political, and cultural change and closely linked to individual and shared norms, beliefs, values, and worldviews (Leichenko and O'Brien 2020). Integrating multiple perspectives, the integrative soapbox approaches climate alter as a transformative process involving the environment as well as communities and our human relationship to nature and each other. By suggesting the metaphor of a living system equally opposed to a mechanistic way of seeing the world, a postmodern and ecologic worldview emphasizes relationships, participation, empowerment, and cocky-organization (Sterling and Orr 2001; Verlie and CCR xv 2018). It recognizes also that questioning paradigms and patterns of thought can create space for new ways of exploring the complexities of climatic change.

Within an integrative discourse, humans are viewed equally a reflexive office of the climate organization that is able to create also as change patterns. This perception introduces the key possibility to alter the relationship that creates climate risk and vulnerability (Leichenko and O'Brien 2019). This discourse is too in line with growing recognition inside the climate alter research community that societal transformations are inevitable in order address the climate challenge (Leichenko and O'Brien 2020; O'Brien 2015; Pelling 2011; Pelling et al. 2015).

Didactics climatic change in arts disciplines using an integrative discourse is an approach that is already being applied in schools in Finland. The Finnish climate guide (Sipari 2016) contains tips and tools for multidisciplinary climate educational activity every bit early as in the primary level. With an emphasis on disquisitional and cultural competence, teachers are encouraged to approach climate change in visual arts courses, music, foreign language courses, and literature (amid other disciplines) (Sipari 2016), for example, through the lens of the ecological handprint that focuses on the positive impacts humans have on the planet as opposed to the ecological footprint that is more problem-centered (Kühnen et al. 2017). While this kind of approach does not require a change in educational activity methodologies, information technology consists rather of a dissimilar content of data and more holistic lens to approach climate change in arts and humanities courses.

Learning nigh climate change with fine art

There is a growing recognition that the electric current dominant model of transmissive didactics is insufficient to meet today's challenges (Blake et al. 2013; O'Brien et al. 2013; Sterling and Orr 2001). Many advocate for a shift from the transmissive, instructive notion of education which relies on the transfer of information to a more than artistic and engaging, transformative learning where significant is constructed in a participative way (Reid et al. 2008; Rickinson et al. 2010; Sterling and Orr 2001).

Seeing with critical optics or critical thinking is a key ingredient in such learning processes. Daniel Willingham (2008) describes critical thinking as "seeing both sides of an upshot, beingness open to new prove that disconfirms young ideas […]." The basic assumption is that we need to "see" differently if we are to know and act differently. Art tin can help usa to see and integrate different perspectives and complexities, which then tin can lead to development of disquisitional thinking. In this research, students adopted a sustainability-related change for xxx days and approached climatic change through a personal experience with change. Along the 30 days, they reflected on the various (personal and systemic) facets of change. This in addition with the group discussions and the artistic expression constituted a student-centered, learning-by-doing approach. Learning with the assistance of creative and experiential approaches has shown to assistance students to find new insights nigh themselves and facilitate new relationships with resources and the topic climate change in full general (Bentz and O'Brien 2019). For example, it enabled i pupil to detect her "own consumerist interior" (student T, written reflection, 2018) during the project. Creative forms of engaging in climate change can assistance students to see things from new perspectives and question their frames of reference. The following quote and artwork from a student (Fig. 1c) shows a critical reflection with the backer way of life, with which she interacts.

I created this paradigm every bit a form of criticism of consumerism, materialism and the greed of mankind, who tries to possess and give monetary value to everything, even to their own planet.

Educatee R, artist argument, Art For Change project 2019

Promoting learning in which students critically examine the structures in which they are embedded is crucial for understanding the causes and impacts of climate alter, and yet is underemphasized in mainstream didactics (Stevenson et al. 2017). Artistic and humanities disciplines at school accept the chapters to promote critical thinking due to fine art'south ability to enhance perspective-taking capacities. Instead of focusing on knowledge provision, teaching tin can involve experiential methods such equally participatory art projects, easily-on labs, field trips, and group dialogues, which engage more than the cognitive domains of learning. The importance of active participation and learning-past-doing is highlighted by the "head, easily and heart" approach to learning, which incorporates transdisciplinary written report (head), practical skill sharing and development (hands), and translation of passion and values into behavior (eye) (Sipos et al. 2008). Such approaches allow students to come across that the shape of knowledge can e'er change and invite them share their ideas in an open way.

According to bell hooks (2010), critical thinking is an interactive procedure, a way of approaching ideas with the aim to empathise underlying truths. Engaging students through interactive approaches tin can be considered a prerequisite of good instruction and a principle of success in environmental education (Monroe et al. 2017). Experiential forms of learning are known for their potential to enable a process of questioning and reorienting existing values, cognition, and concerns (Liefländer et al. 2013). Every bit such, engaging students in deliberative discussions and forms of creative expression can contribute to the deconstruction of students' taken-for-granted frames of reference because it is through the interaction with others that students are exposed to different perspectives and opinions (Mezirow 2000; Monroe et al. 2017). Combining group dialogues with creative and creative expression of learnings and experiences with a irresolute climate, such as in this enquiry, can enable students to see climate change differently likewise as their own role in addressing it. The following quote from a group dialogue shows a sense of responsibleness despite discouraging comments from friends and family almost the student'southward conclusion to eat vegetarian.

People always say things similar "that doesn't practise anything" and maybe I don't see the results. My whole family eats meat and information technology'due south always a topic at the dinner table considering I don't eat the craven. Sometimes I demand to eat another soup or so. I don't meet the difference I am making only you just take to look at it from another perspective. You lot can fix things. Information technology'southward a fact, if we all just stopped eating meat, the meat industry wouldn't exist. So I'chiliad stopping eating meat and a lot of people do too […]. It's changing! Information technology does something.

Student North, grouping dialogue, Art For Change project, 2019

The experiential role in this research, which meant adopting a alter for 30 days in combination with artistic expression, may accept contributed to a deeper cocky-reflection and to the creation of a sense of responsibility. Freire (2013, p. 13) emphasizes that "responsibility cannot exist acquired intellectually, but only through experience." This highlights the importance of the participatory and learning-by-doing components in climate change education. Many artistic methods and practices are inherently experiential. Therefore, they take a great nevertheless seemingly overlooked potential for engagement in and teaching nigh climate change. Pedagogy with art uses unlike forms of teaching. It may involve interdisciplinary projects at school where students reflect on climate change and express the caused learnings within the different disciplines.

Learning about climate change through art

Compared with education in and with fine art, instruction climate modify through art follows a more than radical idea. Where teaching with art tin can be considered participatory and experiential learning that uses art to provide engaging and fun activities, and didactics through art implies letting become of predefined ideas of content besides as of i-fashion directed noesis provision and engage in an arts-led learning process, both for students and teachers. Where teaching with art can be described as an interdisciplinary process in which "art meets science," instruction through art follows a transdisciplinary agenda whereby different ways of knowing (scientific, creative and others) are engaged on eye level (Kagan 2015).

In practice, this means a whole dissimilar arroyo to didactics climate change; one that aims to encounter students where they are at in terms of interests, concerns, and meanings by co-creating the learning process with them and addressing climate change through a topic or lens that is relevant for them. The fact that climate change means different things to different people depending on age, experience, and context supports the idea of making room for exploring those meanings and the associated value systems. Accordingly, enquiry on climatic change meaning-making suggests to connect with the frames and values people hold and fill out pregnant from there (Hochachka 2019). Applying this to a classroom context means for a teacher to translate climate change into something tangible for the students in order to anchor it in their meaning-making. Approaches for meaningful climate change education for young people might need to differ greatly, depending on the specific meaning-making stages of a given classroom, the social context, and value systems.

In this research, students were engaged in storytelling and collective reading of a climate-fiction story (Milkoreit et al. 2016), in which the main graphic symbol is a teenager named Flea, helped to bring climate change near and create meaning, equally the quote below illustrates.

After pushing myself through it and finished reading the story I was very happy with the catastrophe (I think that's my favorite part of the story). Not because it was a happy ending, it wasn't. But information technology wasn't a lamentable ending either. Information technology was reality. I know it's a cli-fi story but the ending got me identifying with the topic. It was when I started understanding the realness of the story. […] It was at the ending that I understood Flea similar I empathize myself, non very well simply well plenty.

Student L, written reflection, Cli-fi & Fine art project 2019

The learning procedure was guided through the storytelling, fiction reading, and the students' personal connections with the subject matter. In connection to that, the students developed an artwork related to a personally relevant topic. A personal connectedness to the topic can tap into students' emotions and senses helping them to come across and call back differently. The potential to connect to emotions and senses makes fine art a profound source for learning (Leavy 2015) and a tool for deepening and embodying experiences. Learning through the body, for example, through movement, dance, or theater piece of work (which was not the case in this research), is another way to connect to emotions and understand theoretical concepts through the senses (Leavy 2015; Wiebe and Snowber 2011). These techniques can enhance the sensation for unlike ways of knowing and increment the degrees of freedom in young people's imagination (Heras and Tàbara 2014). Educatee-centered arts-led processes can thus guide through a significant-making and embodied experience, which can exist a transformative process that enables to see and human action differently on climatic change. The liberty of creative practices tin can help students to explore dimensions and hereafter imaginaries that are non attainable through standard teaching approaches helping them to co-create new scenarios of transformative change. The fiction reading in this research created avenues for creative imaginaries of the future. The artwork 1d expresses the potentiality of scenarios that we ordinarily do not consider. The question "what if the world turns on us," creatively illustrated with a T upside downwards, opens up imaginations of an inverted earth in which non-human agency gains power (Fig. 1d).

Exploring alternative, positive imaginaries of the future can be empowering for young people to co-create scenarios of change such as the artwork entitled "be the drib the globe needs" (Fig. 1e). This is relevant as climate change is increasingly emerging as a depressing force affecting social lives of young people (Ojala 2012). The the artwork 1f illustrates the student'due south helplessness and powerlessness past depicting a person falling into a hole (Fig. 1f).

Acknowledging this trend of psychological stress seems relevant when teaching climatic change. Inside this project, the group dialogues and artistic expression offered students spaces for disclosure and helped them transmuting feelings of powerlessness, hopelessness, anger, and apathy. As important it is to acknowledge the growing sadness, anxiety, and anger when teaching climate, information technology is equally of import to emphasize solutions and opportunities to go engaged. Experimenting with concrete solutions for climate resilience and social transformation through role plays, theater work, or giving actual opportunities for engagement (e.g., local initiatives) can help build a sense of empowerment and hope. Providing possibilities for direct experience in democratic processes, such as through participation in community projects, are examples that enable immature people to come to their ain decisions based on the information they gather and discussions they share (Chawla and Cushing 2007; Hess and Collins 2018). When contextualized in a broader integrative discourse, small behavior changes or school projects tin be empowering too, as they can serve as entry points for larger changes on the political and systemic realm (Bentz and O'Brien 2019). Within this enquiry, the integration of a xxx-mean solar day behavioral modify in a learning-through-fine art approach helped students to realize that their individual choices have an affect globally as well as on others (e.g., family and friends). This realization of one's own power to influence alter can give promise and a sense of empowerment.

There is express research about how to provide transformative experiences in climate change education through fine art (Pelowski and Akiba 2011; Roosen et al. 2018). The success depends very much on the feel of facilitating artists and teachers as well as on the students to embark on a different kind of learning journeying without a predefined destination. The preceding examples prove that within 2 project approaches, 3 levels of engagement can occur. Some students kept their engagement to a more descriptive, shallower one (e.m., Fig. 1a and b), whereas others permitted deeper, more reflexive levels of engagement where they showed themselves more than vulnerable and gained new insights well-nigh themselves and about climate change (Fig. 1c, d, e, and f). Information technology must be noted that non all school settings volition allow working with open up-ended, co-creational, potentially time-consuming processes and the perspective that final results may differ from initial expectations. However, the outcomes of education climate change through arts may profoundly differ from those of engagement in or with art in the sense that they potentially create a deeper bear on on the students, educating them to be empowered, critical and climate active citizens.

Conclusions

In this paper, I take shown how the arts and humanities tin can offering important contributions to the challenge of engaging and learning about climate change. Fine art has multiple potentials that tin be harnessed for climate modify instruction, among them its capacity to engage emotions and to expand imaginaries of the future to create hope, responsibility and care, as well as healing. Fine art is also a powerful form of advice; it tin integrate diverse knowledges through experiential learning and it tin can engage immature people in deeper, embodied, and potentially transformative ways with the discipline (Bentz and O'Brien 2019; Dieleman 2017).

This article aims to offering teachers, facilitators, and researchers a portfolio for engaging with climate change that makes use of the multiple potentials inside the arts and humanities. It provides guidance for the students' interest in, with, and through art and makes suggestions to create links between disciplines to back up meaning-making, create new images and metaphors, and bring in the wider solution infinite for climatic change. The iii categories of using art in an educational context differ in the way they use art. Pedagogy climatic change in arts courses makes utilize of art'south potential to communicate improve but too offers the opportunity to address climate modify from a unlike angle, providing a different content of information (e.g., past focusing on positive examples and ways to influence change). Educational activity climate change with fine art uses of fine art'south experiential potential and invites different forms of didactics and learning every bit well as a different content. Learning through art suggests a dissimilar approach to learning itself guided through art (together with a unlike form of teaching and a dissimilar content) that relies on reciprocity, openness, and co-creation. The stepwise increasing weight of art in the different learning processes can then lead to increasing depths of the students' engagement with the field of study matter.

With the framework provided in this commodity, the depths of engagement and desired outputs of a given learning process may exist amend targeted and addressed. The date may range from an increase of climate sensation, to critical articulation, and sense of empowerment to climate agency and trauma healing. Acknowledging that the boundaries between the categories are blurry, this framework aims to provide a clearer prototype of the spectrum of fine art'due south potentialities for learning and engaging in climate change. This may assist teachers, facilitators, and practitioners to better shape their strategies and adapt them to a given context. It should be noted that the framework is not conceived every bit a recipe for artful approaches and dissimilar levels of engagement may occur within the same group of students or participants, as shown in the results.

The in a higher place examples of learning near climate change in, with, and through art accept certain key aspects in common. Each includes the employ of narrative and metaphors to aid visualize climate modify. They support reflection and deeper meaning-making, and seek to include the emotional aspects of climatic change. They integrate what scholars have seen as the office of schools and the role of art namely to create spaces of possibilities or laboratories of the hereafter where (young) people engage in creative and experiential means with questions connecting socio-ecological modify to the everyday and to their ain experience and shaping not only individual but as well shared desires for potential futures (Dieleman 2012; Fehrmann 2019; Kagan 2015; Roosen et al. 2018; Verlie and CCR 15 2018). They likewise relate to an instruction praxis which accounts for the importance of personal feel in generating agency by creatively identifying problems and solutions through reflection, which in turn produces an appropriate course of action (Camnitzer et al. 2014).

In conclusion, I have presented a novel framework for using fine art in climate change engagement and demonstrated its use in schools. The findings indicate to the central place that art has in climate change education, with avenues for greater depth of learning and transformative potential depending on whether one brings art in to the climatic change curriculum, whether art is taught with other climate science concepts in participatory means, or whether one teaches through the very topic to the heart of transformation itself.

References

-

Barthel S, Belton Due south, Raymond CM, Giusti M (2018) Fostering children's connection to nature through authentic situations: the case of saving salamanders at schoolhouse. Front Psychol 9:928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00928

-

Bentz J, O'Brien 1000 (2019) Art FOR Alter: transformative learning and youth empowerment in a changing climate. Elem Sci Anth 7(one):52. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.390

-

Blake J, Sterling Due south, Goodson I (2013) Transformative learning for a sustainable future: an exploration of pedagogies for modify at an alternative college. Sustainability 5(12):5347–5372. https://doi.org/ten.3390/su5125347

-

Boal A (2000) Theater of the oppressed. Pluto Press, New York, 208 pp

-

Bochner A, Riggs NA (2014) Practicing narrative inquiry. In: Leavy P (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Enquiry, 1st edn. Oxford University Press Inc., pp 789. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199811755-e-024

-

Shush M, Ockwell D, Whitmarsh Fifty (2018) Participatory arts and melancholia date with climate alter: the missing link in achieving climate compatible behaviour change? Glob Environ Chang 49:95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.02.007

-

Camnitzer L, Helguera P, Marín B (2014) Art and education. Publication Studio, Portland, 88 pp

-

Castree, Due north., Adams, W. K., Barry, J., Brockington, D., Büscher, B., Corbera, E., Demeritt, D., Duffy, R., Neves, K., Newell, P., Pellizzoni, L., Rigby, Grand., Robbins, P., Robin, L., Rose, D. B., Ross, A., Schlosberg, D., Sörlin, South., W, P., … Wynne, B. (2014). Changing the intellectual climate. https://www.repository.cam.air-conditioning.uk/handle/1810/247152

-

Chawla L, Cushing DF (2007) Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environ Educ Res 13(4):437–452. https://doi.org/x.1080/13504620701581539

-

Climate Generation (2019) H2o scarcity and perseverance: a humanities module. https://www.climategen.org/our-cadre-programs/climate-change-didactics/curriculum/humanities-content-for-your-classroom/water-scarcity-and-perseverance-a-humanities-module/

-

Cooper KE, Nisbet EC (2017) Documentary and edutainment portrayals of climatic change and their societal impacts. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.373

-

Dieleman H (2012) Transdisciplinary artful doing in spaces of experimentation and imagination. Scribd three:44–57. https://doi.org/ten.22545/2012/00028

-

Dieleman H (2017) Arts-based education for an enchanting, embodied and transdisciplinary sustainability. Artizein: Arts and Teaching Journal 2(2):16

-

Dieleman H, Huisingh D (2006) Games by which to learn and teach near sustainable development: exploring the relevance of games and experiential learning for sustainability. J Make clean Prod 14(ix):837–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.eleven.031

-

Fehrmann S (ed) (2019) Schools of tomorrow. Matthes & Seitz Berlin. https://www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2017/schools_of_tomorrow/schools_of_tomorrow_publikation/publikation.php

-

Freire P (2013) Education for critical consciousness. Bloomsbury Academic, London, 168 pp

-

Funch BS (1999) The psychology of art appreciation. Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen, 312 pp

-

Gabrys J, Yusoff K (2012) Arts, sciences and climate change: practices and politics at the threshold. Sci Cult 21(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2010.550139

-

Hawkins H (2016) Inventiveness, 1st edn Routledge, London, 408 pp

-

Hawkins H, Kanngieser A (2017) Artful climate change communication: overcoming abstractions, insensibilities, and distances: artful climatic change communication. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang viii(v):e472. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.472

-

Heras M, Tàbara JD (2014) Permit'south play transformations! Performative methods for sustainability. Sustain Sci 9(3):379–398. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11625-014-0245-9

-

Hess DJ, Collins BM (2018) Climate change and higher education: assessing factors that bear on curriculum requirements. J Make clean Prod 170:1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.215

-

Hochachka G (2019) On matryoshkas and meaning-making: understanding the plasticity of climate change. Glob Environ Chang 57:101917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.001

-

Hooks B (2010) Teaching critical thinking: practical wisdom. Routledge

-

Kagan Due south (2015) Artistic inquiry and climate scientific discipline: transdisciplinary learning and spaces of possibilities. J Sci Commun 14(01):viii

-

Kirby P, O'Mahony T (2018) The political economic system of the low-carbon transition pathways across techno-optimism. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

-

Kühnen Grand, Hahn R, Silva S, Schaltegger S (2017) Verständnis und Messung sozialer und positiver Nachhaltigkeitswirkungen: Erkenntnisse aus Literatur, Praxis und Delphi-Studien. https://www.scp-centre.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Inhaltlicher_Abschlussbericht_Handabdruck.pdf

-

Leavy P (2013) Fiction as enquiry practice, 1st edn. Left Declension Press, Walnut Creek

-

Leavy P (2015) Method meets art: Arts-based research exercise, 2nd edn. Guilford Publications, New York

-

Leichenko R, and O'Brien K (2019) Climate and gild: Transforming the futurity. Polity Printing, Cambridge

-

Leichenko R, O'Brien Chiliad (2020) Instruction climate alter in the Anthropocene: an integrative approach. Anthropocene 30:100241. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.ancene.2020.100241

-

Lesen AE, Rogan A, Blum MJ (2016) Science communication through art: objectives, challenges, and outcomes. Trends Ecol Evol 31(9):657–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.06.004

-

Liefländer AK, Fröhlich K, Bogner FX, Schultz Prisoner of war (2013) Promoting connection with nature through environmental educational activity. Environ Educ Res 19(3):370–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.697545

-

Mezirow J (2000) Learning as transformation: disquisitional perspectives on a theory in progress. The Jossey-Bass college and adult educational activity series. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco

-

Milkoreit 1000, Martinez M, Eschrich J (eds) (2016) Everything modify an anthology of climate fiction. Arizona Country University, https://climateimagination.asu.edu/everything-modify/

-

Monroe MC, Plate RR, Oxarart A, Bowers A, Chaves WA (2017) Identifying effective climate change education strategies: a systematic review of the research. Environ Educ Res, 0(0), one–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

-

Moser SC, Dilling L (2011) Communicating climatic change: closing the science-action gap. Oxford Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0011

-

Norgaard KM (2011) Living in denial: climate change, emotions, and everyday life. The MIT Press

-

O'Brien K (2012) Global environmental modify II: from adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog Hum Geogr 36(5):667–676. https://doi.org/x.1177/0309132511425767

-

O'Brien K (2015) Political agency: the key to tackling climate change. Science 350(6265):1170–1171. https://doi.org/10.1126/scientific discipline.aad0267

-

O'Brien K, Reams J, Caspari A, Dugmore A, Faghihimani Thou, Fazey I, Hackmann H, Manuel-Navarrete D, Marks J, Miller R, Raivio 1000, Romero-Lanka, P, Virji H, Vogel C, Winiwarter V (2013) Y'all say yous want a revolution? Transforming education and chapters building in response to global alter. Environ Sci Pol 28:48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.011

-

Ojala M (2012) Hope and climate change: the importance of promise for ecology engagement among young people. Environ Educ Res 18(5):625–642. https://doi.org/ten.1080/13504622.2011.637157

-

Overland I, Sovacool BK (2020) The misallocation of climate research funding. Energy Res Soc Sci 62:101349. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.erss.2019.101349

-

Pelling Yard (2011) Adaptation to climate modify: from resilience to transformation. Routledge, New York

-

Pelling M, O'Brien Thou, Matyas D (2015) Accommodation and transformation. Clim Chang 133(1):113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1303-0

-

Pelowski M, Akiba F (2011) A model of art perception, evaluation and emotion in transformative aesthetic feel. New Ideas Psychol 29(ii):lxxx–97. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.newideapsych.2010.04.001

-

Reid A, Jensen BB, Nikel J, Simovska 5 (eds) (2008) Participation and learning: perspectives on didactics and the surround, health and sustainability. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/ten.1007/978-1-4020-6416-vi

-

Rickinson M, Lundholm C, Hopwood N (2010) Environmental learning: insights from inquiry into the student experience. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2956-0

-

Roosen LJ, Klöckner CA, Swim JK (2018) Visual art as a manner to communicate climate modify: a psychological perspective on climate modify–related art. Globe Art 8(1):85–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2017.1375002

-

Ryan Grand (2016) Incorporating emotional geography into climatic change inquiry: a case study in Londonderry, Vermont, USA. Emot Space Soc nineteen:v–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.02.006

-

Saldaña J (2016) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications. https://united kingdom.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-coding-manual-for-qualitative-researchers/book243616

-

Schreiner C, Henriksen EK, Hansen PJK (2005) Climate didactics: empowering today's youth to meet tomorrow'due south challenges. Stud Sci Educ 41(1):three–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260508560213

-

Shrivastava P, Ivanaj 5, Ivanaj Southward (2012) Sustainable development and the arts. Int J Technol Manag 60(1/2):23. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2012.049104

-

Siegner AB (2018) Experiential climate modify pedagogy: challenges of conducting mixed-methods, interdisciplinary research in San Juan Islands, WA and Oakland, CA. Energy Res Soc Sci 45:374–384. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.erss.2018.06.023

-

Siegner A, Stapert Due north (2019) Climate change education in the humanities classroom: a example study of the Lowell school curriculum airplane pilot. Environ Educ Res 0(0):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1607258

-

Sipari P (2016) Teacher's climate guide. Teachers Climate Guide. https://teachers-climate-guide.fi/

-

Siperstein Southward, Hall Southward, LeMenager S (eds) (2016) Teaching climatic change in the humanities: 1st edition (paperback) - Routledge. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Teaching-Climate-Alter-in-the-Humanities-1st-Edition/Siperstein-Hall-LeMenager/p/book/9781138907157

-

Sipos Y, Battisti B, Grimm K (2008) Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int J Sustain High Educ 9(1):68–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370810842193

-

Sterling South, Orr D (2001) Sustainable teaching: revisioning learning and modify. UIT Cambridge Ltd.

-

Stevenson RB, Nicholls J, Whitehouse H (2017) What is climate change education? Curric Perspect 37(1):67–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-017-0015-9

-

Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What we think nigh when we try not to think about global warming. Chelsea Greenish Publishing. https://www.chelseagreen.com/product/what-we-think-about-when-nosotros-try-not-to-think-about-global-warming/

-

Veland Southward, Scoville-Simonds M, Gram-Hanssen I, Schorre A, El Khoury A, Nordbø G, Lynch A, Hochachka G, Bjørkan M (2018) Narrative matters for sustainability: the transformative part of storytelling in realizing 1.5°C futures. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 31:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.005

-

Verlie B, CCR fifteen (2018) From activeness to intra-activity? Bureau, identity and 'goals' in a relational arroyo to climatic change didactics. Environmental Didactics Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1497147

-

Vethanayagam AL, Hemalatha FSR (2010) Issue of environmental education to school children through animation based educational video. Language in India x:10–16

-

Wiebe South, Snowber C (2011) The visceral imagination: a fertile infinite for non-textual knowing. J Curric Theor 27(2). https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/commodity/view/352

-

Willingham DT (2008) Critical thinking: why is it so hard to teach? Arts Instruction Policy Review 109(4):21–32. https://doi.org/10.3200/AEPR.109.4.21-32

-

Yusoff Thousand (2010) Biopolitical economies and the political aesthetics of climate. Theory, Culture & Guild, Change. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276410362090

Acknowledgments

I limited deep gratitute to the students and teachers of Escola Artística António Arroio, Lisbon that were involved in the research, especially to Jerónimo de Sousa. I am grateful for constructive feedback and excellent edits of Karen O'Brien, Gail Hochachka, Irmelin Gram-Hanssen, Milda Rosenberg, and Morgan Scoville-Simonds.

Funding

This piece of work was funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência eastward a Tecnologia in the frame of the projection UIDB/00329/2020 and with the support of CICS.NOVA - Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences of the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, UID/SOC/04647/2019. The writer is supported by a BPD grant SFRH/BPD/115656/2016, with the financial support of FCT/MCTES through National funds. The conception and framing of this article started in a writing retreat supported by projection AdaptationCONNECTS, University of Oslo.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Admission This article is licensed nether a Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, equally long as you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary party material in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you lot will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Bentz, J. Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Climatic Modify 162, 1595–1612 (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10584-020-02804-iv

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02804-4

Keywords

- Sustainability instruction

- Transformation

- Arts-based methods

- Youth

loveactereptur1964.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-020-02804-4

0 Response to "Apathetic Integrating of Art and Music in the Middle School"

Postar um comentário